In the northern Okinawa village of Ogimi, a stone marker displays the declaration of village elders that reads “at eighty you are merely a youth, at ninety if the ancestors invite you into heaven, ask them to wait until you are one hundred… and then you might consider it.”

In the northern Okinawa village of Ogimi, a stone marker displays the declaration of village elders that reads “at eighty you are merely a youth, at ninety if the ancestors invite you into heaven, ask them to wait until you are one hundred… and then you might consider it.”

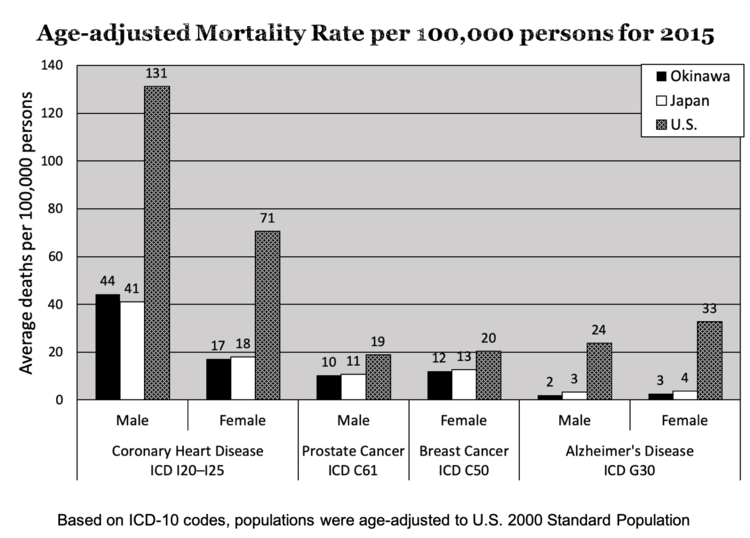

The significance of Okinawa’s health phenomenon can be appreciated by considering a typical age-associated disease and its impact upon a typical city of 100,000 inhabitants in Okinawa, Japan and the United States. For coronary heart disease (CHD)—the leading cause of death in the United States—if the city was located in Okinawa, about 3 times fewer males and more than 4 times fewer females would have died from this ailment in a typical year, than if this was a city in the United States. That is a striking difference.

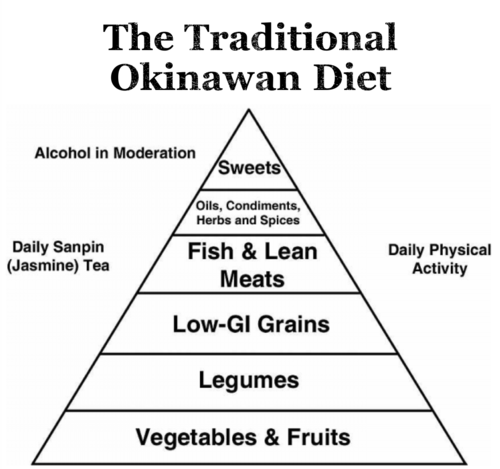

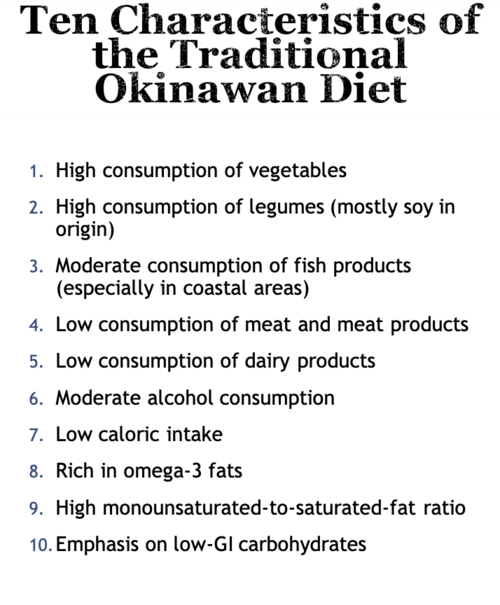

In fact, the traditional Okinawan diet shares many characteristics with other healthy dietary patterns, such as the traditional Mediterranean diet or the modern DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) diet. Low levels of saturated fat, high antioxidant intake, and low glycemic load in these diets are likely contributing to a decreased risk for cardiovascular disease, some cancers, and other chronic diseases through multiple mechanisms, including reduced oxidative stress.

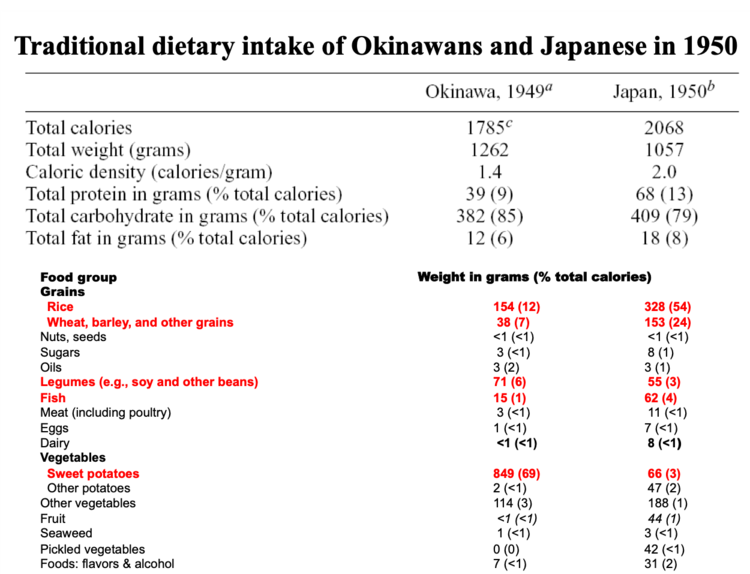

In Okinawa, the low-calorie, phytonutrient-rich and nutritionally dense food choices, the healthy eating habits, and high levels of physical activity resulted in a naturally calorically restricted population without malnutrition. In the traditional dietary habits, there was a focus on small portion sizes and not eating until completely full. Even now a common saying among Okinawan elderly is hara hachi bu (eat until only 80 percent full). We estimate that Okinawans prior to the 1960s consumed 10-15% fewer calories than would normally be required per caloric guidelines (Willcox et al. 2007 PMID: 17986602). When faced with a persistent energy deficit, mammals adapt by becoming more energy efficient, producing less heat and converting a higher proportion of food into usable energy. A host of other metabolic adaptations occur that confer longevity. These changes are commonly observed in animal studies of “caloric restriction” (CR) and this is the only consistently reproducible manner of increasing mean and maximum lifespan in animal experiments, other than select genetic manipulations. (Fontana et al. 2010 PMID: 20395504).

Additionally, the traditional Okinawan diet appears to be a rich source of foods that may mimic the biological effects of CR, acting as caloric restriction “mimetics.” CR-mimetics are compounds that provide the physiological benefit of CR without the need for restriction of calories through multiple mechanisms, including reduced oxidative stress. In the Okinawan language, a common parlance is “nuchi gusui,” which can best be translated as “let food be your medicine.” This reflects the cultural context wherein the distinction between food and medicine blurs in Okinawa and deeper analyses reveals that many of the traditional foods, herbs, or spices in the Okinawan diet have medicinal properties, which are under investigation (Willcox & Willcox 2014 PMID: 24462788).